![]()

This past summer, I hit the hot streets of Marrakech, Morocco with Lomography’s new LomoChrome ’92 film in a Canon AE-1 SLR camera with a 50mm lens.

LomoChrome ’92 ISO 400 is supposed to bring the “unforgettable energy” of the 1990s, promising accurate colors and “powerful” film grain; I feel like it really lived up to that last part.

I shot my last roll of film back when I was a teenager, so maybe I’d forgotten, but I was taken aback by how grainy the photos were. Particularly the ones taken in lower light. I can hear the eyes rolling around the heads of analog shooters as I state the obvious but light is so, so important in film photography.

Not that light is unimportant in digital, of course it is, but after years of relying on Photoshop to get me out of a bind when the RAW pictures didn’t look great straight out of camera, it underlined to me that you can’t push a 35mm negative anything like the same way you can push a RAW digital image.

Shooting

I was so nervous loading the film into the camera — I was terrified I was going to get it wrong. Fortunately, the Canon AE-1 is one of the best-selling SLRs of all time and there were plenty of guides out there to babysit me through it.

Marrakech is an amazing location and it seemed the light there was made for film photography. I was there in summertime with temperatures around 113 degrees Fahrenheit (45 degrees Celsius) — water was essential.

I was told before I went that people in Morocco might not appreciate the camera. Full disclosure, I ended up paying a little bit of money to the people whose portrait I took (5 dirhams or so which is a little over a dollar.)

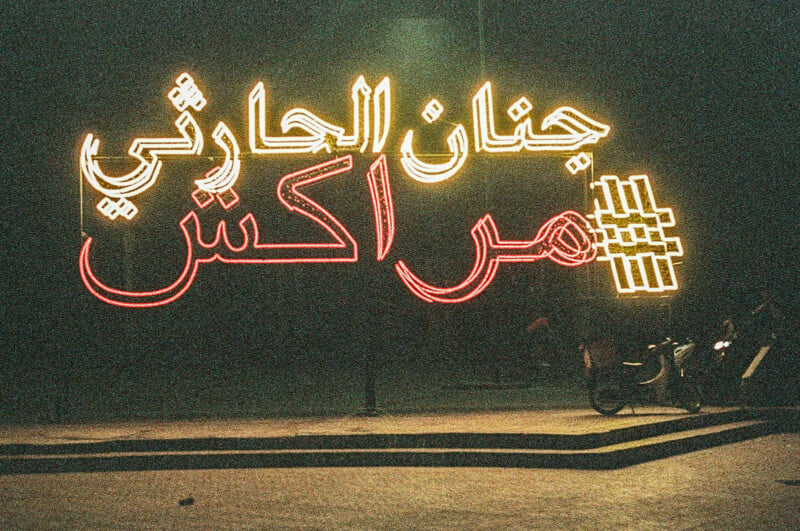

Virtually everything is financially negotiable in Morocco and the subject of a portrait is no exception. I took my film camera to Jemaa el-Fna, the main square which is alive with snake charmers, exotic food, and market stalls. There are heartbreaking sights there too like monkeys with chains around their necks.

It was an exciting challenge and I enjoyed approaching people to ask for a photo. I felt the pressure when taking photos: Judging my exposure settings from the meter reading inside the viewfinder and focusing manually before I fired the shutter and wound the film cassette (my favorite part).

The Photos

I was excited about the photos when they were still on the roll of film. A few of them stood out to me, such as the portrait of a Berber I took (Berbers are indigenous people who predate Arabs in North Africa).

But the Berber portrait came out horribly — all washed out and grainy. I think I overexposed it which didn’t help things and at that point of the day the light was sub-optimal. Lesson learned.

The other photos were hit-and-miss. I somehow made a double exposure; I was aware this is a feature on the AE-1 but I have no idea how I made it but it actually turned out kind of cool because I got the shape of the Koutoubia Mosque, Marrakech’s tallest building, silhouetting a main road.

Conclusions

I wasn’t enamored with my photos. It took me months to find a lab to get them developed and when I got them I was disappointed enough to drag my heels on writing this article.

I heartily doff my hat to film shooters, how do you do it? How do you shoot photos that you can’t instantly get a read on and keep plowing money into an archaic medium? It’s too stressful. After years of digital, I need to see what I’m shooting.

But having said all that, I loved the process of shooting film: the tactile nature of it all, the beauty of the camera, the lack of screens. If I did it again, I would have a better understanding of the exposure settings and be more conscious of the light I’m shooting in. Maybe I won’t wait another 20 years to shoot my next roll.

Image credits: Photographs by Matt Growcoot.