BlueSuburbia is an exploration of a world that seems to revel in your agony, all eyes on you to watch as you suffer. Even so, there is beauty and poetry to the journey as you explore a world that brings various art styles together, letting you wander through fields where 3D art and Bitsy are mired together. It’s a striking look at the shining possibility and misery of games all at once.

Game Developer had a chat with Nathalie Lawhead, creator of BlueSuburbia, to talk about the complexities of getting various game-making tools all working within Unreal, its exploration of how people’s pain is often treated as entertainment, and the heavy responsibilities developers carry when exploring complex emotional material with their works.

Game Developer: BlueSuburbia is a march toward hope through a world that seems to revel in your destruction. What inspired the creation of this experience?

Lawhead: The very first BlueSuburbia from the late ‘90s was about my family’s experience with the Balkan War, and many of the themes dealt with poverty and refugees. Secretly making it while in high school was my way of dealing with the culture shock of moving to America. There was always this throughline of hope in a terrible, consuming darkness. You are your own light, as illustrated by the original version, which changed your cursor to a tiny light flame. Some individualistic strength to find beauty in hopelessness.

The new version deals a lot with how it was for me to come forward about my sexual assault and how game media treated that. The correlation in most of these experiences is an understanding of the way society alienates people that have to deal with terrible things. People that are hurt are either a source of entertainment or a talking point to criticize to no end. They don’t fit in a world with perfect people who are living happy successful lives because they broke out of that imagery and are reflections of how the world really is.

I’m trying to make the experience that BlueSuburbia is about more general—not just about myself—because I think art should be able to speak to everyone’s experiences. Everyone struggles with horrible things. Everyone carries pain with them. I think there is a power in art to be able to bring people together with a universal sense of solidarity. To me, art has always been about speaking truth to power.

What drew you to create worlds to wander mixed with poetry? What appealed to you about finding meaning through exploring place and words?

What strikes me about video game spaces is their intentionality. The level of detail that you are able to imbue them with is such an intentional act. If you see cracks in the concrete, it’s not just because concrete has cracks in the real world, but it’s because an artist took the time to make those in that very specific way… scratches, dust particles floating in the air, writing on the wall… Every detail adds to the story of a space—omission of detail as well. I think there’s something powerful about how surrealist you can make a video game space as a result. It’s a world that you stand in, that an artist created with absolute intent, and it’s the closest thing you can get to standing in someone else’s dream.

It’s such a beautiful concept to explore when you want to bring poetry to a space. Spaces are stories. Spaces are poems. Exploring what it means to exist in a space is something that I think is uniquely beautiful about video games.

I’m trying my best not to just think in terms of text, but that the spaces are a way to illustrate the writing.

The game delves into several different visual styles. What drew you to explore all of these different forms of visual expression? What interests you about doing this with your works?

Switching between visual styles is a good way to change the mood of what you are experiencing. For example, each character that you talk to has their own font associated with them. The way UI’s degrade around certain text can convey that character’s tone.

I think it can become a powerful way to influence mood when you embrace what may feel like inconsistency. When you stick with just one art style, it can become boring, and the experience stops feeling “new.” If you can balance the way you shift through visual themes, I think it’s a stronger way of communicating.

There’s this charm to illustrating the space you are in by switching between 2D and 3D. For example, at the beginning, you are greeted with a Bitsy that illustrates your journey into the first space. It’s very low-fi. You kind of get the first impression by using your imagination to fill in between the gaps. Then, it drops you off into the actual space you experienced in the 2D context. There’s something novel about letting a player be in a video game space using all the different ways at our disposal. It’s a much more impactful way of delivering writing than just text in the corner of the screen.

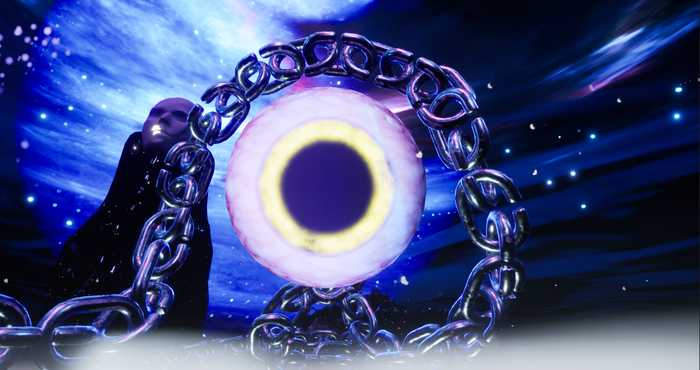

BlueSuburbia is filled with striking imagery and effects. Can you tell us a bit about how you created the visual effects and looks, mechanically?

There was certainly a huge learning curve for me. I wanted to create everything completely on my own. A lot of work went into learning how to properly work with post-processing effects and making textures that looked as out-of-this-world as possible.

With every space, I spent a lot of time in Blender to make textures that looked hyper-realistic, and then spent time working to translate that into Unreal to maintain that detail.

I’m pretty sure I tried every trick in the book to optimize textures as much as possible. I had no idea what texture streaming was, or all the pitfalls behind open world development, before this. It was a lot for a first 3D game, but I figured if I was going to do something in 3D, I should embrace everything about it.

Each space has its own visual style that’s tied together with hyperrealistic-looking textures. What I loved about old 3D games, or the promise of 3D from the late ’90s era, was the fixation on hyperrealism… like it was so real that it came back around to looking fake. Games like Myst were hugely inspiring to me. Myst was an iconic breakthrough in games. I think that type of 3D is beautiful to mix with older low-fi visual styles because it’s kind of a nod to the history of visual styles associated with computer games.

To my knowledge, you worked with both new and old game-making tools to create BlueSuburbia. Can you tell us about the work that went into learning these new tools and into weaving them into the systems you already knew? Also, can you talk about the work that went into bringing them together?

There’s a treasure trove of tiny game-making software out there. Like Bitsy, Pocket Platformer, Decker, Pico8, and so many fantasy consoles, I can’t name them all. They’re all created with simplicity in mind, where value is placed on technical restrictions. Each has their own focus on what they find important about games, so each lends itself beautifully to their own very specific niche type of gameplay.

I spent a lot of time getting these to run within Unreal. Most of them are browser-based, and will run locally, which is fairly easy to pull off with Unreal because of the Web Browser Widget and the flexibility of Unreal’s UI system.

It’s a lot of fun to do. You can even embed them in 3D widgets to have these other game engines run inside your game world. The flexibility it gives you in terms of storytelling is huge. For example, there’s a monitor sitting in a pool of dark water in the main menu. If you click on it, you can run the Flash version of BlueSuburbia (emulated with Ruffle) and play that on the 3D monitor. There’s so much layer and dimension that you can give your work if you mix these tiny tools and engines with the big thing. You could go on forever with rabbit holes and tangents for players to explore.

Since BlueSuburbia is all about exploration, that was an important technical thing to nail down perfectly.

What drew you to the imagery you used for the game?

I love how intrinsically surrealist games are. With how buggy they can get, especially all those endearing quirks in popular triple-A open world games, it often seems like their natural state is to be surrealist, weird, or nightmarish, and developers have to work hard to keep them from being that. I think it’s special if you can just embrace how weird they are and use that as a conduit for abstract surrealist art. Most of the imagery from BlueSuburbia was about conveying painful topics by means of surrealism. For example, in the old Flash version, there’s imagery like butterflies flying around a rose that’s sitting on a column in a dark world surrounded by ruins, and crosses come from the sky to bomb them by dropping pills on the space… Like it doesn’t make sense out of context but within context, given the journey to that space, it weirdly makes sense. You explore poetry through exploring surrealism and metaphor.

Were there any unexpected things that happened while designing the visuals and worlds? Any pleasant, unintended things that you kept within the game itself?

When I was learning post-processing effects, most of the best effects were happy accidents. A lot of the glitchy effects are things I had no intention on using but ended up using because doing them intentionally didn’t look as good. Unreal is a beautiful tool for inventing happy accidents that are better than anything you could come up with intentionally.

In BlueSuburbia, everyone can hear you scream

You excel at creating unease, terror, despair, hope, and beauty, creating constantly mixed, almost-overwhelming feelings throughout BlueSuburbia. How do you weave so many complex emotions into your work? What thoughts go into making a work that captures challenging, tangled feelings?

I think when you approach difficult topics, there’s power in surrealism. Metaphor means something different to everyone because it’s abstract enough that they can read themselves or their own experiences into it. So, you make a space where people can think about themselves and the world in a comfortable and safe way.

One of the biggest criticisms of the original BlueSuburbia was that there’s no “story” or goal. It was about reading poetry in spaces that illustrate the poems. Understandably, this version still has that “issue” because it will always be about reading, but I’m building a story around it that gives context to all the poetry you find.

The game starts off with talking about you journeying far with a heavy burden you were never able to share, trying to find freedom from it. As you journey through the spaces, you find characters that point you on a path to that freedom, but it’s all extremely metaphoric. By keeping it open to interpretation, there’s a type of relatability people find in it if they’re willing to really be immersed in the experience.

I think reactions to this type of work are interesting, too. If you come in looking for a proper game with goals, and skip all the writing, the main complaint is that it doesn’t make sense. If you actually come in at a slower pace, read the writing, and use the spaces to think about yourself or your life, people generally find it very meaningful.

It’s hard to balance that type of experience, especially when people expect a certain pace from a video game.

What challenges do you face when doing the writing for BlueSuburbia? What sort of work goes into getting the ideas down just right and conveying your meaning with care without overburdening the player with excessive details? How do you write with clarity while making room for player interpretation?

I have a very general goal with the type of story I want to tell with it. You wake up, wandering through this endless journey, losing yourself while carrying a heavy burden. You find characters that acknowledge that pain and try to either help you or dissuade you from finding freedom. Eventually, you learn that, to be free from your burden, you have to be willing to destroy yourself. So that’s where you find these metaphors for how society treats survivors.

The writing heavily informs how the spaces are created, but often, the spaces have me change the direction of the writing. 3D game development is very different from 2D. 2D experiences can direct the player to certain outcomes much easier. When you have 3D, you have all sorts of directions and factors that you have no control over, or even know how a player will behave in the scene. You can’t be very controlling or direct. You have to leave a lot to personal exploration and discovery. Understanding how a player might engage with a space (2D or 3D), and being flexible with your desired emotional outcome, is important.

While this experience is designed for the player to find meaning as they explore, creation can also be an exploration of the self. How has creating BlueSuburbia been an experience in exploring yourself and your life as a creator? Has it taught you anything about yourself? How has its creation affected you?

It’s kind of a fun journey because I’m recreating this thing I made in the late ’90s, early 2000s, while I was a teenager in high school. Looking back at a lot of it is almost like reading your old high school poetry. It’s kind of cringy. A bit embarrassing, maybe. Often, you hope nobody will see it, but it was out there, and a lot of people saw it.

Going back over these themes to bring them to a new level of artistic maturity is a self-reflective challenge. I want to honor the person I was back then by doing justice to what BlueSuburbia always was, but also I find a lot of the themes too angsty to include. I’m glad I get this do-over.

In creating affecting works, you can stir up powerful feelings in the player. Does this worry you at times? What dangers do you feel exist in touching the player deeply? What benefits come from putting these experiences out into the world?

Yes. I think there is a risk of being too overbearing with themes of hopelessness. Sorry for being too blunt, but I’m often in that place where I wonder what the point of living is. I know that I have to be careful not to pour that feeling into my work because just the fact that it’s interactive, a game, and a space that requires someone else to exist in, can be too overbearing or hurt them. There’s an artistic responsibility to provide hope and personal power and highlight personal strength. Even if, as an artist, I might not feel like that sometimes, there’s no point in making art that robs the viewer of hope without any good reason.

It’s important to have art that talks about heavy, triggering, traumatic topics. You need that. These things exist. We should go there. At the same time, you have to provide a level of aftercare to the person playing. You have to think about how this thing will affect the player. You have to care about the light at the end of the tunnel, building on feelings of solidarity, or encouraging empathy. There’s more to art that’s “traumatizing” than just being sad. It’s building on these deeper connections that matter the most.

BlueSuburbia unflinchingly tackles the commodification of misery for entertainment and mass consumption—of burning a life to cinders just to watch the fire dance and see how much ad revenue the sparks can bring in. What do you hope this experience stirs in the people who play it?

It’s hard to admit, but to some extent, we all do that, don’t we? We like to look at the morbid thing that happened to someone. To speculate. We like watching true crime, or thrillers with big scary stabby serial killers who are portrayed as these hot monsters, or buddy cop movies where the police violence is often a punchline… It’s hard not to get uncritically sucked into that culture when you constantly see documentaries about these serial killers who are very much platformed to a point of cultural reverence.

We really don’t think about what this does to people victimized by that. There’s no space for victims to really reclaim agency over their own stories and tell them their own way. Social media especially exasperates that when everyone with an account can come down on someone victimized and ask them all these terrible prying questions because that horrible thing that happened to someone is now a talking point. I don’t think there’s quite a word to describe what it’s like to watch all these strangers openly talk about the horrible thing that happened to you, speculate about all the ways it’s your fault or that you’re a liar, and see those conversations get actual honest to god engagement. It’s all just entertainment. The people participating move on with their lives. You stay stuck in that, so it’s kind of like an extension of the horrible thing that already happened to you. It’s a culture.

When you experience that for yourself it’s really hard to look at all these documentaries about serial killers, or TV shows glorifying certain brands of violence (sorry for sounding Like That), without seeing a little of what happened to you in it.

So, all that said, it drives me up the wall when people brush off games that deal with the artist’s personal trauma as “just one of those trauma games.” Like, we have a right to talk about it too; it’s reduced to entertainment in literally every other facet of society. As clumsy as these modes of personal expression may be, there’s an element to taking your own power back. It’s about building empathy, understanding, compassion, and rejecting the type of society that works so hard to destroy victims while defending the abusers.

That’s what these types of personal autobiographical games mean to me, and it’s what I’m trying to bring to BlueSuburbia.