In early 2023, the United States Supreme Court released its opinion in the case of The Andy Warhol Foundation vs. Lynn Goldsmith.

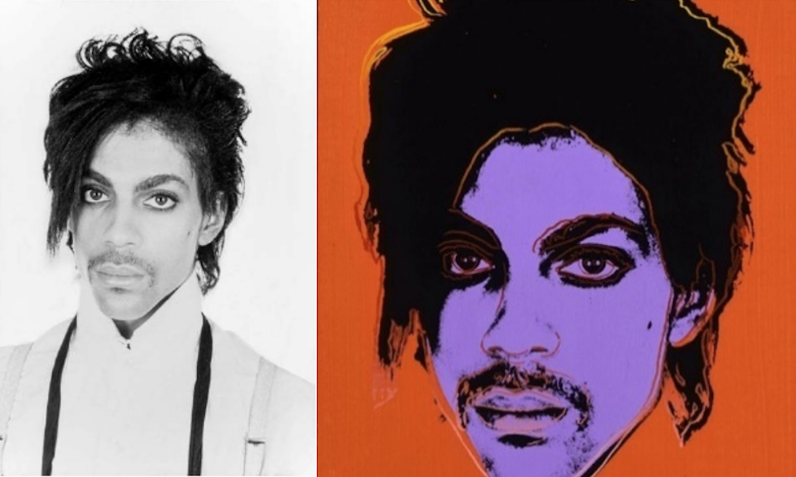

To recap briefly on the Warhol case for the unfamiliar: Over several years, photographer Lynn Goldsmith fought the Andy Warhol Foundation over its re-use of a famous photo she’d captured of the artist Prince.

Goldsmith argued that artworks created by Warhol from her black & white studio photograph of Prince violated her copyright over the photo because they retained the essential elements of the original image.

A Circuit court judge in New York agreed with her, stating, “Crucially, the Prince Series retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements.”

Vanity Fair magazine licensed one of Goldsmith’s photos of Prince in 1984 for an illustration of Prince for an article on the musician. Later, the same photo was used by Andy Warhol as a reference for a famous piece he created.

Warhol then went on to create another 15 works based on that original image. These were called the “Prince Series” and Goldsmith was unaware, at first, that they were created.

After Warhol’s death, The Andy Warhol Foundation retained the rights to his works, including the Prince Series.

In 2016, shortly after Prince died of an overdose accident at his home in Minnesota, the foundation licensed the use of these prints to Conde Nast (the parent company of Vanity Fair) for a commemorative issue about Prince.

This is when Goldsmith became aware of the existence of the Warhol prints and their use by the AWF for commercial purposes.

She then finally registered her photo of the artist with the U.S. Copyright Office and also informed the AWF that they were infringing on her copyright.

The AWF then actually sued her first, preemptively, claiming that they were engaged in fair use with their licensing of the Warhol artwork derived from her photo.

After further legal wrangling via suits, countersuits and appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court definitively agreed with Goldsmith in early 2023 through an 87-page, seven-to-two opinion.

This hefty judicial finding essentially states that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo was not transformative enough to warrant fair use and does indeed violate her copyright.

Many Press and Photographer’s associations celebrated the ruling as a win for the profession and its creators.

One legal expert, Thomas Maddrey, Chief Legal Officer and head of National Content and Education at the American Society of Media Photographers even predicted afterward that “The importance here cannot be overstated,”

He added that the case would have wide-ranging implications in the arts community and for all kinds of intellectual property due to its improved definition of what transformative changes mean in the context of fair use.

Also, considering how new decisions can be further expanded and reinterpreted by courts, the Goldsmith ruling showed broad potential to affect artists and photographers in many copyright contexts.

These predictions are now manifesting themselves in unique ways.

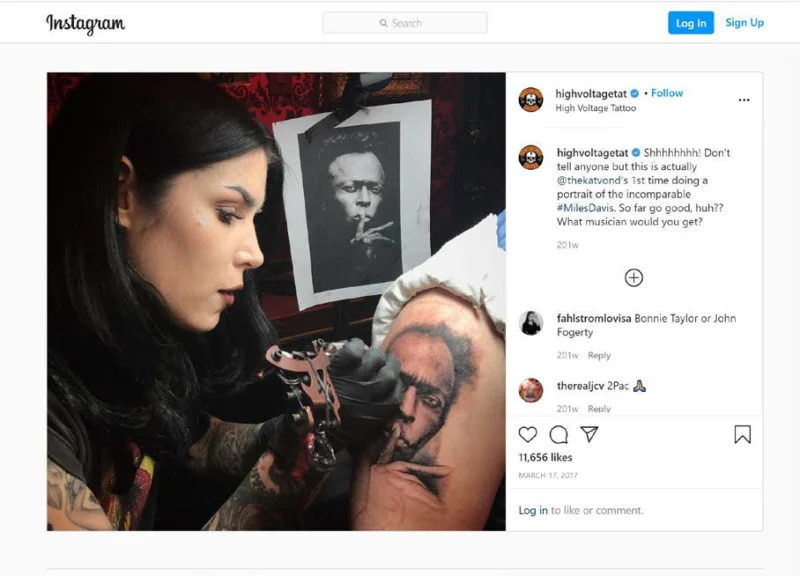

One recent case involved photographer Jeff Sedlik, who sued celebrity tattoo artist Kat Von D for using his photo of the jazz musician Miles Davis on a tattoo for a client.

He argued that it wasn’t fair use due to the tattoo’s exact replication of the photo on a person’s skin.

While Sedlik filed his lawsuit against Kat Von D (Katherine Von Drachenberg) in 2021, a U.S. District Court Judge paused the whole case to wait for the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on the Goldsmith/Warhol suit.

However, despite the Supreme Court ruling in favor of the photographer, Goldsmith in the Warhol case, Sedlik wasn’t so lucky.

The judges and jury in his case, fortunately, ruled in favor of Kat Von D, ruling that a tattoo inked out for a friend by hand was not a violation of fair use.

Despite this, Sedlik, and his lawyer argue differently and plan on appealing (even going as far as to claim that the Instagram popularity Von D received from the tattoo was a part of her violation of his copyright claims.)

In response, Kat Von D’s lawyer, Alan Grodsky stated, “This case should never have been brought,”

He added, “It took the jury two hours to come to the same conclusion that everybody should have come to from the start: That what happened here was not an infringement.”

As the NY Times notes, Shubha Ghosh, an intellectual property law professor at Syracuse University, commented that this case could have had all kinds of implications for derivative creative works in the arts,

“If Kat Von D had lost, the case’s stakes could have had far-reaching consequences, Ghosh said. For one thing, tattoo artists might have become more cautious about the kind of work they take on.

“If you’re a tattoo artist, somebody comes in and says, ‘I want to get this tattooed on my body,’ you now have to worry about, ‘Well, who has a copyright of that thing you gave me?’” Ghosh said.”

Obviously. While it’s easy to sympathize with Lynn Goldsmith in her case, where an essentially exact replica of her photo was widely commercially reproduced without her knowledge, the Kat Von D case is different.

In the latter, a tattoo artist hand-inked a tattoo (free of charge apparently) of a sketch she’d made from a copyrighted photo of Miles Davis. There’s a distinct difference in process, scale, and intent in those details.

A screenshot from court filings of Kad Von D’s IG post about the Miles Davis tattoo

Curiously, Jeff Sedlik, in his capacity as both photographer and copyright licensing expert, was an expert witness for Lynn Goldsmith during her court fight with the AWF. He even stated at one point,

“The right to create derivative works – and importantly, to control the creation of derivative works by others — is one of the primary exclusive rights enjoyed by creators under copyright law.

This also applies to works that are created in another medium, such as creating an illustration, painting, or woodcarving based on a photograph, or adding color to a black and white photograph, or other similar modifications or re-executions of a photograph in another medium.”

Nonetheless, the Goldsmith ruling continues to reverberate in favorable ways for still other photographers. One other recent example of this involves photographer Larry Philpot.

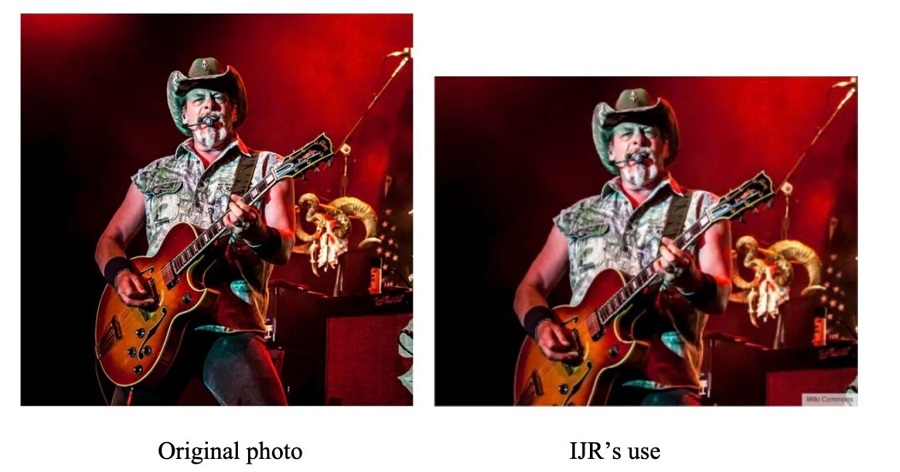

In 2013, Philpot registered a photo he’d taken of famous country musician Ted Nugent with the U.S. Copyright Office as an unpublished work.

However, he also published his photo on Wikimedia Commons under a Creative Commons license that let anyone use the image for free as long as they gave attribution to him.

In 2016 the website Independent Journal Review snatched up a copy of the photo for an article titled “15 Signs Your Daddy was a Conservative”

Crucially though, they gave no credit to Philpot.

This breached their automatic obligations under his Creative Commons license conditions for the photo and in turn Philpot eventually filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against the Independent Journal Review in May of 2020.

An initial ruling ruled in favor of Independent Journal Review claiming that the use of the photo was transformative because it was placed in the context of an article written by them.

Last month though, the U.S. Court of Appeals reversed this ruling and stated that the Independent Journal Review hadn’t exercised fair use since almost nothing notable about the photo was altered before republishing it.

The court documents also argued that the Independent Journal Review “stood to profit” from its use of the photo.

Despite earning no more than $2 or $3 in ad revenue for the image (the website doesn’t charge readers for reading its pieces, but does make money off in-article ad revenue), this was still considered a commercial re-use for motives of profit.

Philpot’s context for his lawsuit and victory was in many ways quite different from that of Lynn Goldsmith and the AWF’s reuse of her photo, but the bigger case likely had a heavy influence on the ruling in favor of Philpot.

In this case too, a commercial entity, the Independent Journal Review, was slapped by a stricter definition of fair use into ceding legal defeat, and we’ll likely see more of the same unfold down the road.

If you’re a photographer with your images out there under fair use or other legally ambiguous copyright conditions, these new legal findings could help protect your work.

On the other hand, if you’re a creative artist who uses other artists’ images for derivative purposes, it’s a good idea to carefully check their copyright conditions and measure just how much “transformation” you’ll be applying.

If you’re both a photographer and an artist who uses others´ photos for your work, good luck navigating both sides of the playing field!

Header image credit: Library of Congress

Highly Recommended

Check out these 8 essential tools to help you succeed as a professional photographer.

Includes limited-time discounts.