The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

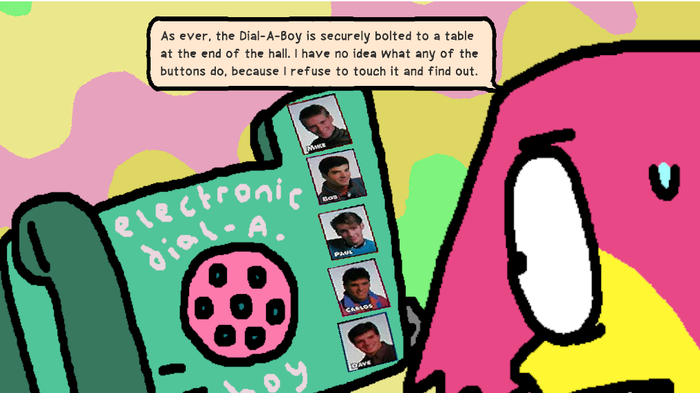

Anthology of the Killer follows BB through her surreal, bizarre, scary, and ridiculous adventures at forbidden museums, spooky music scenes, and lost zine distros.

Game Developer caught up with Stephen Gillmurphy and Tommy Tone to discuss the way serial narratives tend to go to strange places over time and how this lead to the creation of this game, how the oddball nature of video games as a medium makes it easier to take stories to strange places, and finding ways to surprise even yourself with the results of your own work.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Anthology of the Killer?

Stephen Gillmurphy: My name is Stephen Gillmurphy aka thecatamites aka garmentdistrict and I did art, writing, and other things for the games. The soundtrack was composed by Tommy Tone.

What’s your background in making games?

Gillmurphy: I have spent the last 20 years developing award-winning erotic mahjong titles such as Olivia’s Secret and Scramble Garden 2, and sometimes making hobbyist entertainment software in between. The latter titles are more known in the indie scene and include Space Funeral, Goblet Grotto, and 10 Beautiful Postcards.

Images via thecatamites

How did you come up with the concept for Anthology of the Killer?

Gillmurphy: I was interested in trying to make narrative games and especially a serial narrative, since I always admired the strange places those can end up in—like the way the General Hospital soap operas eventually involved aliens and a weather machine, or all those “two gamers on a couch!” webcomics where you check back after 200 installments and now it also involves aliens and a weather machine. In general, I like the idea of doing something over and over until the edges blur and it becomes gradually more strange.

At some point I read the English translation of Junji Ito’s Uzumaki for the first time and got really excited by it. It was a serial horror narrative where the individual chapters kind of split between Nancy Drew-ish mystery storytelling and startling surrealist imagery that seemed to belong to a completely different narrative order. So it made me feel like you could do anything you wanted with “horror.” Also, people sometimes say horror stories need a disposable protagonist to work, but to me, it actually heightened the effect to have these images presented in a monster-of-the-week way with a recurring heroine pulled into one situation after another.

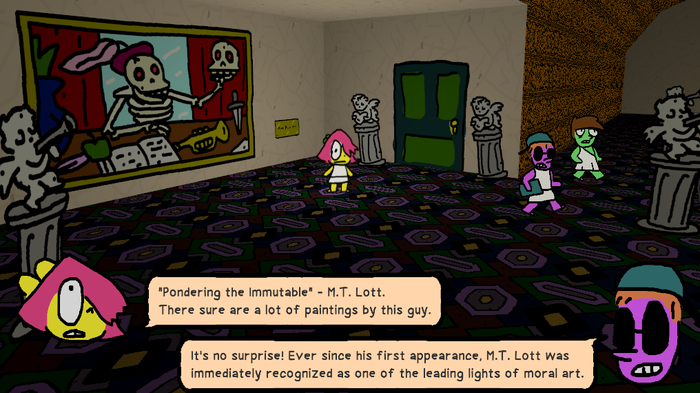

The Haunted PS1 stuff also kicked off while I was becoming more interested in horror, which I felt excited by. It felt like “art games” had gotten a bit glossy and professionalized these last few years and so I was glad to see people picking up the scrappier end of those techniques and using them for inventive Roger Corman-y exploitation purposes. It was nice to feel like I was working on the margins of a different scene.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Gillmurphy: It was made in Unity for my sins. The main reason was to use Fer Ramallo’s “Doodle Studio 95” plugin which is a really quick way to draw sprites into a 3d game, and accounts for a lot of the art style. Given Unity’s general dubiousness over the last few years I also enjoyed “going all out” for one last spin around the program and trying out all the different fussy assets like cloth physics, the ProBuilder plugin, a narrative one called Fungus, mirror and water effects from the asset store, etc. [I’m] entering my 70s cokehead producer period.

The world of the Killer games flows into all sorts of wild, weird, hilarious, and absurd places. What thoughts go into creating an episode and the places/events we’ll see within? Into creating this seamless connection between extremely different places and events?

Gillmurphy: I feel like credit for this goes to the horror genre itself which always has weird old forgotten bits of history surfacing in strange ways—unsettling combinations of the old and new—slasher-like collage techniques, etc.. There’s a Lucio Fulci movie which ends on the line “No-one will ever know whether children are monsters or monsters are children. – Henry James” and the idea of inventing a totally spurious line from Henry James of all people just to add some zazz to a horror film is really delightful to me. It feels like we already live in a period full of odd connections so it’s almost more a case of trying to remain aware of them.

Also, video games are a good format for exploring that…I feel like in books and movies, connections between one scene and another, can only be left obscure for so long before I get distracted by trying to figure out how it fits. I don’t believe anyone has this problem in video games, where the wildest leaps still “work” as long as you control the little guy moving across them. “Well, I went here and then I went there. I collected the things, it all made sense at the time, and now it’s over. What’s the issue?”

What ideas go into making the visuals and effects for these surreal places? What ideas go into creating the visual style of these games and the dizzying effects that fill many of them?

Gillmurphy: A lot of my favorite parts in b-movies have nothing to do with the scene’s plot content—it’s more like this magpie approach to adding visual interest regardless of anything else that’s happening. Taking advantage of odd places, memorable wallpaper, character actors with interesting faces or outfits, startling camera angles or lighting decisions. I feel like there’s something generous in the idea that the screen always has something to look at even if you’re checked out of anything that’s going on.

Images via thecatamites

The game is filled with all manner of interesting characters and creatures. What ideas go into their designs? What makes a creature feel like it’s a good fit for these games?

Gillmurphy: I have a big reference folder of interesting masks, video game monsters, paintings, etc., but it’s very uncertain whether I’ll be able to correctly draw any of them. A lot of the time, I start by trying to draw something straight and then mangle or combine things in the process. For example, the lion monster from Flesh Of The Killer started out inspired by one of those golden Mycenaean death masks and then the snout from a decayed-looking animal statue got mixed in. I have a hard time doodling anything bigger than a thumbnail so anything that’s still legible at that scale is hopefully both distinctive and uncluttered enough to work in the game!

Anthology of the Killer mixes humor and horror very effectively. What appealed to you about mixing disturbing events and ridiculousness?

Gillmurphy: I feel like, for both comedy and horror, to do them completely straight you have to prioritize the audience’s response above your own; you have to know when to pile on an effect even when it’s something you personally have less of a response to, as the person behind the scenes. But I think I still have this selfish child conception of game making, like “Wow… a game that’s just for me!”, and so have a hard time picturing how other people will react.

Since I experience the games at a slightly removed position, I always want to make something that will still “work” at a distance—where there’s enough going on that you can still find it interesting even if you’re not totally bought into one or the other effect. And for some reason the sense of slipperiness, when something shifts between responses in an uncertain way, still resonates for me even when I’m the one making the game, so I always end up aiming for that feeling as a result. I am basically looking for some combination of elements which will mystify me even after I’ve put them all together myself.

But I’ve tried to be sincere with the horror part of the games, and to make sure that however goofy they end up, there’s always some little kernel of an idea or image buried in there that genuinely upsets me. The mixture of horror and comedy does that more than straight horror. I remember being scared as a kid by a rented copy of the game Zombies Ate My Neighbors. The pastiche tone meant it could present the world as an endless maze of haunted dolls and masked killers without the usual ways we frame and contain those images. I think horror and tragedy prioritize the singular, exceptional moment, which is at least something that ends. Comedy deflates those moments by folding them back into continuity with the everyday, which can be more unsettling since it means there’s no way out [laughs].

What thoughts went into creating the music for Anthology of the Killer? With the game exploring so many moods and surreal places, what difficulties did you face in creating varied music for this game? What benefits also came from the varied feelings and places?

Tommy Tone: I’ve been collaborating with Stephen now for just about 13 years on various other independent games; I feel like we both have a good sense of each others musical and artistic sensibilities. When I started making music for these games, I was using this synthesizer module called a Yamaha FB-01. It’s incredibly limited, but working within those limitations produced some really unique compositions. Over the course of this series I’ve made music with software VST plug-ins, too. I’m not one for sticking with a certain music making process for too long. Changing things up keeps me on my toes. Specifically for this series, musicians like Dām-Funk, Daniel Pettuci, Saveur Mallia, Elaine Radigue, Sky Douglas, DMX Krew, and Inoyama Land were huge inspirations to me.

What styles of music felt right for this experience? How did you find a cohesive audio core for Anthology of the Killer?

Tone: I’ve had a number of DIY electronic/punk/noise side-projects over the years, so I’m not put off by going out on a limb and trying some out-there ideas if it’ll produce an interesting result. One of the newer songs for this game was constructed entirely from a recording of me hitting my bathtub, slowed down and looped to create this gradually developing sense of unease. I’ll gladly throw that in next to a joyful 30 second looping song that seems never-ending. Or a song that wouldn’t be out of place in a Hallmark movie.

Besides a general guideline that is provided through early builds, I’ve had a lot of freedom to write music for this game series. I’m grateful for the mutual trust Stephen/thecatamites and I have built over the years. It allows me to try out some really unconventional ideas when the mood strikes me.

Images via thecatamites

These games are a nonstop onslaught of funny moments and things to see. What thoughts go into cramming so many laughs into every part of the game? What challenges do you make in ensuring there’s something funny in pretty much every interaction?

Gillmurphy: Mostly I have the jokes first and then adjust the plot to find a place to use them, sometimes combining locations arbitrarily if they don’t have enough material on their own to work as single areas, or sticking in bits of unused plot to make things feel good and dense. By the time I’ve done all this, the original jokes I was planning out no longer seem that funny to me and are usually thrown away or recycled later…I hope this gives the areas and plot movements an uncanny feeling, like event architecture built for a purpose that is never specified and never actually takes place.

Also, when revising the game, I try to put in more jokes in the writing to keep things nice and breezy on a moment to moment level as you’re walking around… I feel like sufficient breeziness can actually end up being as good for mystery as really opaque and esoteric writing, because your attention span slides off of exactly what is being conveyed. So hopefully it works as a way of keeping things mysterious without signaling “mysteriousness.”

Can you tell us a bit about the development process in making an episode? How you build out an idea into a world and story?

Gillmurphy: Aside from the first one, they all sort of start as responses to the previous episode—trying to fix parts I wasn’t happy with, or as a way to change things up. The game Blood Of The Killer (about multiple murderers chasing each other around a small town) was kind of a response to the immediately previous game Flesh Of The Killer, which was more a creature feature about being chased around a museum. I wanted to make something more gory and horror-toned than the cartooniness of that one, and I thought setting it mostly outdoors would be an interesting change. I also wanted to have a busier plot with more maniacs.

Sometimes ideas come up with one game that I don’t have time to explore until the next. When making Flesh Of The Killer I looked at Henri Rousseau’s jungle pictures for reference on some areas. But while doing that, I found I was really interested in his quiet, strange pictures of the Paris outskirts. So, I had to wait until the next game to be able to make something exploring that mood. When I have an outline, I also try packing in anything I think would be fun to explore in that setting, any jokes I’ve been meaning to use, and such.

I make the levels in order from start to end and try to improvise off the structure in my head since some stuff doesn’t work in practice, other stuff works better than expected and I end up wanting to explore it more, etc… After every few areas I stop to figure out if the rest of the outline in my head still works or if I need to change it up to stay interested. I always feel like the only ideas I trust are ones that come up in the course of development, so the plot at the start of the game is more or less just an excuse to hunt for truffles.

This is how I make all my games and for all I know is just how all video games are made, so apologies if it’s repeating stuff everyone already knows. But I feel like it explains a lot about why my games come out the way they do.

Are there any ideas you’ve had that you cut from the game? Can you tell us about some of those and why they didn’t feel right or work out?

Gillmurphy: Mostly it’s ideas I either can’t do or can already do too competently for them to go anywhere interesting. For example, I wanted to make a game where the main character is sick in bed with a fever for the whole thing, her own daydreams mixing with the daytime TV she’s half-watching, wandering dream areas and being chased by her own subconscious image. It felt too broad to structure, like it would require a lot of new visual work without knowing whether or not I’d have to trash it all, and I didn’t feel like I had any ideas about dreams or the inner life that weren’t just cliches.

Conversely, I had an idea about a zine fest being cannibalized by venture capital guys but that was almost TOO easy to plan out and I didn’t feel like I could surprise myself with it. I feel like the best idea is something I don’t really know how to do properly but where the misshapen quickie version of it could still end up being interesting.

What benefits came from developing smaller episodes instead of one colossal storyline all at once? Were there any downsides to working this way?

Gillmurphy: It’s been really nice to be able to go “Oh well, ship it, I’ll make up for anything that doesn’t work NEXT time”… Since I have a day job I like projects where I can just fire up the engine and start working away without having to come up with a lot from scratch, so it’s been nice to mix that approach with games that are a little smaller and more focused. It’s also been nice to let things simmer more—to have characters and ideas pop up as needed and then to let them sit as I wait for a chance to reuse them again, rather than trying to cram in everything at once. I’m looking forward to bringing some older characters back for the last entry in particular.

The downside is just not feeling able to enjoy that between-projects feeling since even when I finish releasing a new one, I’m already thinking about the next in the series. I don’t want to drag things out further than they have been [laughs].

What sort of feelings do you get from working on something meant to make people laugh (and be horrified a bit too)? How does it feel to work in humor with your creations?

Gillmurphy: The most fun I have working on things is coming up with stuff that makes me laugh so it’s been very nice to get to spend so much time doing that. Also, due to streaming and seeing the games played live at Southside Games in Glasgow I feel like I’ve gotten to see people’s responses to them more than usual. There’s something pleasantly circular about finding an idea I thought was funny, spending several months on development and releasing and so forth, and then the same idea comes out the other side and someone else thinks it’s funny too.