This is about the horror of liminal spaces, and the intrinsic surrealism of our digital world… That beautiful awful loneliness of existing in the electric void of shared virtual fantasies that video games are.

Video games are the closest thing that we have to existing in someone else’s dream. Carefully constructed fantasies that we share with players. These are our fever dreams, both pleasant and awful.

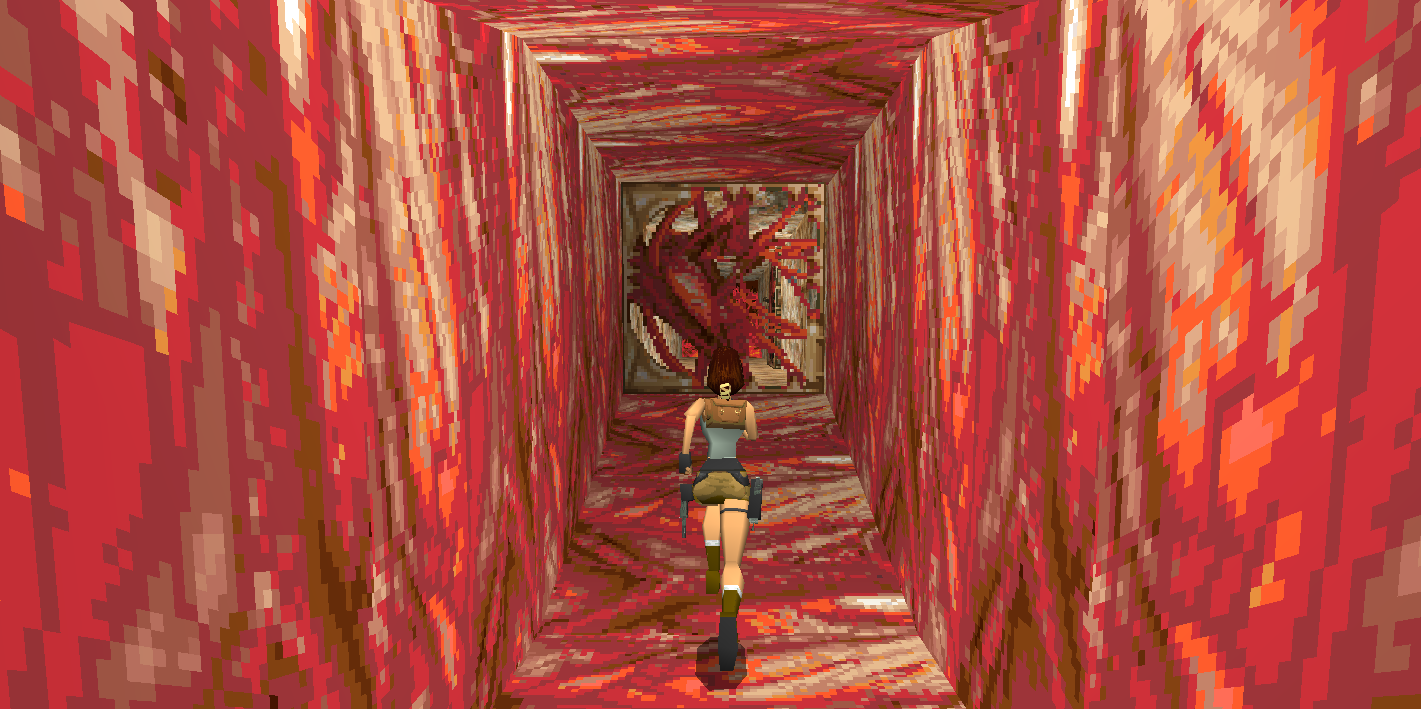

Tomb Raider 1, Level 14: Atlantis

Computers lend themselves well to horror, surrealism, or absurdist expression, because (at heart) the concept of computers does not make sense.

The fact that we created this very virtual, non tangible, inherently ephemeral and transitional “world” outside of our physical reality is fascinating to reflect on. None of this is real. This post isn’t really either. It exists only as 0’s and 1’s, unless you print it out. Then it’s part of a tangible reality.

Our virtual reality is an electronic ephemeral concept that is something of an expression of our collective conscience, for good or bad… but so much of this “not real” is vital to our daily existence.

If you look at it that way, then we’ve created a weird dependent symbiosis between computers and people. Computers are strange things, easy to break and prone to malfunction, but behind that malfunction lies the realm of our beautiful and often terrible virtual nightmare.

Since working on BlueSuburbia, I can’t get enough of that feeling. If you’ve encountered it at any formative part of your digital life then you know what I mean!

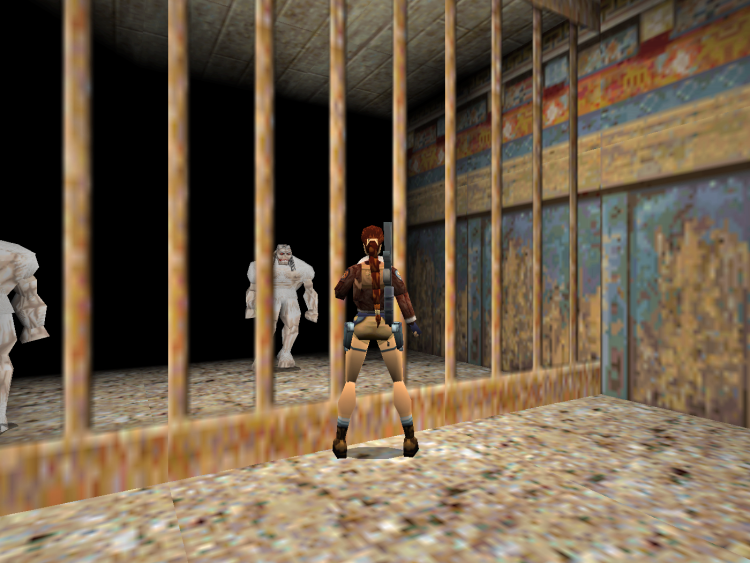

Old school video game terrors: Tomb Raider Yetis, Tomb Raider’s Great Wall level, the sad zombie in Space Quest XII, and Alone In the Dark (original)

My go-to games when growing up were PC games. DOS games, or demos collected from demo disks.

(Tangent: I recently found these again and was over the moon! So many memories!)

The iconic low-fi graphics we now relegate to “nostalgia” is something I remember viewing as often terrifying. It had a unique “I’m alone and I don’t want to be in this place” feeling.

The lack of detail meant you could read so much more into it, especially fear.

My initial experience with games like Alone in the Dark and Tomb Raider often still surpass anything today (I speak for myself, that’s not a generalization).

Maybe we rely on too much when we place so much value on visual fidelity? Maybe horror is elsewhere?

Despite the incredible depth of detail AAA games today have, I think the older lack of detail, the hidden things, what remains unsaid… is why horror in games remains such a unique experience. This is why I think the PS1 era style horror boom is so popular right now. I wrote about that here: Exploring the beautiful world of indie horror games (why work from smaller devs, and indie devs, is so meaningful)

The loneliness of Tomb Raider’s Tibetan Foothills was awful… Or even the dread of having to go into Tomb Raider 2’s Yeti Cages is something that will always highlight how terrifyingly lonely crawling through video game spaces can be. There could be more in that darkness than just low-poly Yeti’s! What if!?…

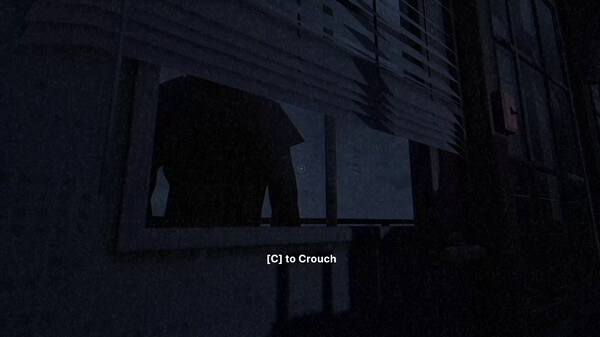

“This is an indie horror game with first-person puzzles. Terror and fear have enveloped the city. The maniac has returned. You sneak into his lair to try and stop him before he goes too far…”

The terrifying menace of loneliness is a unique quality to three-dimensional spaces. If I watch a horror movie, I am with the protagonist. I am a witness, but not alone. If I’m in a video game, then I have to be the protagonist. I am alone.

Fears to Fathom – Ironbark_Lookout

“Jack Nelson, a 24-year-old fire lookout, transferred to a new outpost. As he settled into his new home, he couldn’t shake the feeling that something was off, little did he know what was transpiring down in Ironbark State Park.”

Our digital horror is electric nightmares, embracing the wacky brokenness of machines, and what remains in our collective memory after it becomes nostalgia… This is what existing in these surrealist nightmare is all about.

Via Assasin’s Creed bug photography Twitter Video games sure get unsettling when their carefully crafted worlds bug out.

I’m often humored that video games seem so naturally broken and buggy. We have to work really hard to make them not be that way. So much work is put into making cloth behave like cloth (not clip through a body, which if it happened IRL would be true horror), or keep characters dressed (no spontaneous nudity), or keep weird bugs from happening (try any open world AAA game on launch day and you know what I mean)… So much work is done to get games to behave. They are naturally absurdist, ridiculous, surrealist…

Horror here is when we embrace their natural state: really weird fever dreams.

Video game horror is more than a next-gen high quality aesthetic. It doesn’t have to have rich evocative three-dimensional environments. It can range from strange drawing apps, overblown malfunctioning UI’s, or using your actual file browser to put you into a dungeon like Dungeons and Directories does. (Which I’m overjoyed to know about.)

When I made Cyberpet Graveyard I looked everywhere for similar experiences that use the way a computer functions (anything native to a desktop for example) to tell a story. Dungeons and Directories is a creative example!

Computers are fantastic places, and games are the accumulation of our digital fantasies. It doesn’t have to be in carefully built and curated worlds, it can also be the way we just exist in our daily digital lives that becomes the platform for playing one.

It doesn’t just have to involve an explicit definition of play. It can be something that’s just strangely different like the animated gif drawing program LIPSU.

LIPSU is one of the coolest, wackiest, loudest, drawing tool ever, with a UI that’s equally as astounding. I can’t believe more people aren’t talking about it. Make art with beautiful trash and get wild animated gifs reminiscent of a digital apocalypse. It’s robots dreaming of electric sheep beautiful. The menace of being trapped in a terrifyingly glitchy app that you draw in with uncontrollable digital effects is an amazing experience.

If you look at it all in these contexts, then it begs the question: what is our digital reality?

That having been said…

Our digital spaces are ephemeral. Nothing lasts. Not even the games we make will be playable forever. This digital art is a constant waterfall of new games, lost games, forgotten games, and “there are too many games” arguments… Words like liminal spaces, transient spaces, dreamscapes, and fever dreams, best describe how it’s like to exist as a digital artist.

It’s all so breakable and easily lost.

Playing games involves passing through uncounted virtual environments, much like existing in the real world does. You are always passing through a space… all these spaces, the in-between parts of the journey you don’t really pay attention to. There’s something beautiful to the idea that so many of these game spaces, that were so relevant as we were experiencing them, are often lost on us. Like dreams, we forget once we wake up… Or, in this case, close the program.

After enough time, the game might not be accessible anymore… virtual worlds slowly deteriorate and die, servers are shut down. We lose virtual spaces all the time. They are ghosts.

To me, it’s beautiful food for thought to think about how that fits into horror. What are video game spaces to our collective unconscious?

“”Father’s Day” – a psychological thriller that is a spin-off and prequel to the game “Find Yourself”. The dream of living happily ever after was destroyed after Phil lost his wife and son. Obsessed with the desire to return them, he develops a plan.”

There’s a lot that hides in these digital shadows.

“‘The Guest’ is a gloomy adventure full of enigmas where the exploration of your surroundings comes to prominence; puzzles, secrets and riddles will help you discover who has locked you in this somber hotel room and most importantly, why.”

There’s a subtle terror to everyday common spaces that horror often taps into. The invisible places that you don’t really see because they exist just to pass through. Transitional journeys are a concept that define games. I talked more about “the joy of existing in virtual spaces” here, but examining how this is particularly evocative in horror games is interesting. There’s a weird relatable terror to be found in the ephemeral and liminal!

Maybe that’s why the liminal spaces trend is so popular on Instagram. I fell down an Instagram rabbit hole looking at backroom lore. It’s like social media horror folktales… What’s beautiful about it is how “video game” it always looks. It almost wouldn’t be the same if it wasn’t for the “uncanny valley” effect that 3D art gives it. For example: this, this, or this… I love following how people run with that.

Because of that fascination, I started getting recommended games in a similar gist!

Which is a fascinating “recommended for you” loop to find, especially for how evocative video game spaces are. They can slowly grind you down every-time you are asked to round a corner and step into a new unknown. There’s a unique menace to this overwhelming feeling of loneliness found in these games. The horror is not so much what physical harm may happen, but in the solitude of just being there.

Dreamcore (demo only, coming soon)

“Dreamcore is a body-cam styled psychological horror game based on the “liminal spaces” aesthetic. Immerse yourself in Dreamcore’s mysterious universe by exploring non-linear worlds and solving puzzles.”

Games like Dreamcore build on the backrooms concept as a video game. I played the demo and found it fascinating how there’s not necessarily anything out to get me, try to kill me, or any threat of immediate harm, but it still manages to put you on edge in both a serene and unnerving way. The dark corridors in the distance, the very bright windows you can’t see through, stranger and stranger swimming pools… There’s a through-line of horrible loneliness in many of these games that I think is worth acknowledging. Being alone with yourself in a strange uncertain place can be a uniquely upsetting experience.

“You are trapped in an endless underground passageway. Observe your surroundings carefully to reach “The Exit 8″.”

I found out about The Exit 8 on Instagram. The use of an innocuous everyday space like a subway that you can’t escape is a beautiful idea. It’s like P.T. but well-lit. There’s something particularly unnerving about being trapped in a loop, with white noise from the fluorescent lights constantly pouring into your ears, and that one stranger that you keep walking past. As you keep looping around, the environment incrementally becomes stranger. The space is what attacks you. I think it’s a novel achievement because it does so much with very little. The threat of loneliness is real here.

In a similar “alone in a public space” vein, with more complexity, is Find Yourself…

“Explore the truly frightening subway cars and find out what fears the main character will have to face.”

While judging for The Webbys I found Unknown Number: A First Person Talker. “An innovative voice-controlled adventure game, played through a series of interactive ‘phone calls’. Join the heist and save the world… using nothing but your voice.”

I think it’s an accomplishment for how these seemingly mundane UI’s (webpages, phone interfaces…) become so tense. The way the story is told in that game is amazing. I keep saying it: UI is a space too! 2D can be just as atmospheric as 3D.

Don’t Scream has a similar mechanic by using your microphone to make sure you “don’t make a sound” otherwise you die. It’s surprisingly hard to stay quiet. The novelty of a game breaking through the fourth wall like that, by involving another aspect of a player’s input (sound), makes for a well constructed upsetting experience. The horror isn’t just happening to the video game protagonist. It’s actually happening to me.

“If you scream, you restart. An Unreal Engine 5 short horror experience made by two indie devs. The challenge: explore the forest for 18 minutes without screaming. The catch? Time only ticks when you move. It’s the perfect game to scare the pants off your friends and family. MICROPHONE REQUIRED!”

I love that you can now live in a found footage movie!

Don’t Scream is constructed beautifully, controlling the scope just right, along with an iconic horror visual style, to make you feel like you’re in a proper found footage film. It’s also a notable accomplishment for how it appeals to Streamers, because they all have to play it while talking very gently. If you can get Streamers to keep their commentary to a whisper, then you’ve achieved the impossible.

(Sorry) jokes aside, the tangible tension that you feel from playing this, while trying not to talk, is a slow burn. I think it’s unique for how it combines all that exceptionally well. It might not hit the same if you play it alone. It’s not hard to stay quiet when playing something solo, but if you try to involve other people (stream, play with friends), it’s a truly difficult thing to power through.

Fears to Fathom – Ironbark Lookout also uses player voice feedback in a create way to build on the horror. I highly recommend that one!

If you scream, the video game monsters find you.

I think there’s something powerful about using environments in a video game as the main horror component, best illustrated by examples in this post: Dreamcore, The Exit 8, or (of course) P.T.

The actual space the player is placed in is a monster too.

Video games seem so uniquely qualified for that. They empower us to place players in these actual contexts that we would not be able to in other linear media. The player becomes part of the world, not just a passive observer.

Even if it’s not straight up horror, the way games lend themselves to surrealism is special.

Like I keep saying, video games are the closest thing we have to being inside of someone else’s dream. A world specifically created just for that one experience… to share these fantasy spaces that offer an escape into something bizarre, surreal, and yet unseen.

BlueSuburbia is my own forray into this. I just recently released it on the Epic Games Store… It’s also on Steam Early Access, and itch.io.