![]()

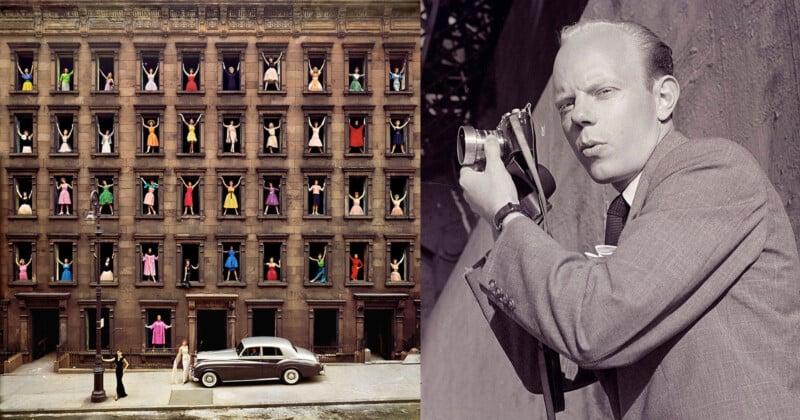

Ormond Gigli (1925-2019) is an American photojournalist with a career spanning over forty years. But today, he is mainly known for one photo – Girls in the Windows – that he created in 1960. It shows forty models and women posing in the window frames of a brownstone about to be demolished on East 58th Street in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, an affluent New York neighborhood.

The New York Times on Nov 21, 2023, in an article titled Is This the World’s Highest-Grossing Photograph? spoke with an auction house specialist. ‘We’ve had discussions about this internally,’ said Caroline Deck, senior specialist of photographs at Phillips in New York City. ‘It must be the highest-grossing photograph of all time.’

This piqued our curiosity to learn more about this image and the photographer, who is not a household name in photography. Ormond created it for himself without an assignment just to remember a bygone era. It was a massive undertaking under severe deadline – the building was to be demolished in two days, 40 (plus two on the sidewalk and one on the first floor) models or women in colorful outfits had to be organized, permission from the building demolisher had to be sought, a huge hole in the sidewalk had to be filled, and a loaner Rolls Royce Phantom had to be parked at the base.

The Making of a Masterpiece

“He was sitting in his studio one day and looked out the window across the street, where they’re tearing down, I think, it’s two brownstones [from the previous century],” Ormond’s son Ogden Gigli tells Peta Pixel.

“All the windows were taken out, and he thought to himself, what if I put a woman in every window? He thought about it, then talked with his staff and had to make it happen the following morning [as they would begin the demolition the next day after that].

“They called the model agency, and he walked down to the corner where the Rolls Royce dealership was and asked them if he could use [borrow] it [for the shoot]. He called Con Ed[ison] to fix a [large] hole in the sidewalk.

“And then he did the picture two hours later [starting at noon during the workers’ lunch break], and it only took a couple of hours because that’s all he had to do it [in] because of construction [demolition]. And he just had to get it done.”

Ormond shot Girls while standing on the second-story fire escape of his studio with a bullhorn in hand from where he could distinctly see and direct the action and spread out the colors across the brownstone’s five floors. Girls almost looks like colored toys or dolls in a doll house.

The story goes that the demolition supervisor said he would allow the shoot provided it included his wife in the photo – and she was standing on the third floor, third from left. In a pink outfit (currently aged 95), Ormond’s wife, Sue, is also there on the second floor, far right.

Ormond was concerned for the models’ safety as some brave ones were posing on the collapsing sills and in heels as the glass windows had already been removed.

As has often been said about good photos, Ormond did not take a photograph, he made a photograph.

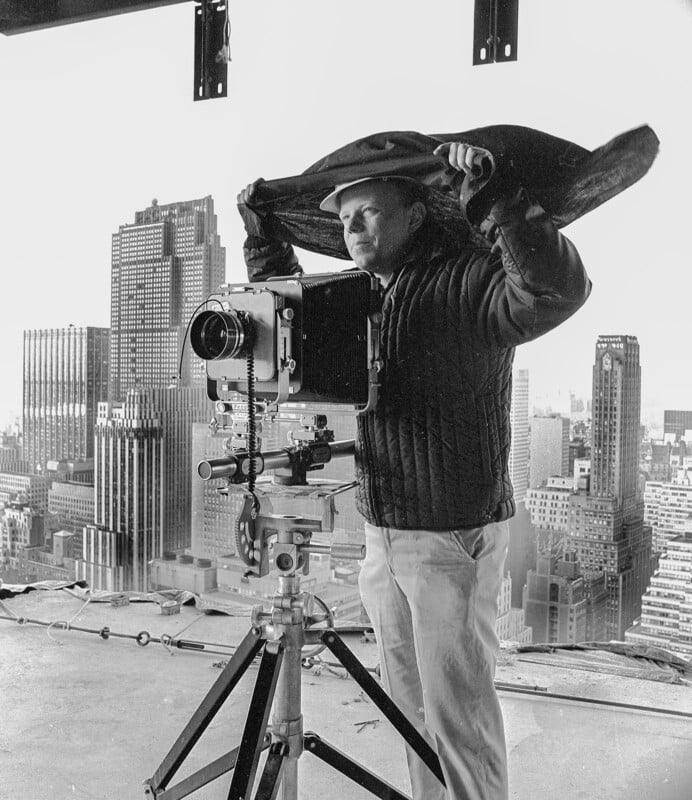

The Cameras and Films of Gigli

“He used a Graflex and also a Hasselblad, and so there’s black and white and color,” recounts Ogden, also a photographer with a studio in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, nestled in beautiful Berkshires, who considers himself very fortunate to be able to make a living in a field that he feels so passionate about.

The Graflex was a 4×5 Speed Graphic camera and used sheet film. Ormond used Ektachrome slide film in the Graflex. Ogden does not remember which B&W film was used but thinks it was probably Kodak Tri-X. The Hasselblad was either the 500C or Hasselblad 500CM.

“Everything in color was shot with the Graflex,” continues son Ogden. “He himself printed a lot of black and white. He preferred it in black and white. I love the color, but [with] the black and white, there’s just something about it that I love. The building just looks really like the period of 1960.

“[He] didn’t shoot that many. I would say he shot five or eight rolls [of 120 films giving 12 square 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ inch exposures per roll] and probably ten sheets.”

“First, it [the original 4×5 slide] was copied to an 8×10 inch [transparency]. And then that was scanned with a beautiful drum scanner and that’s what we’ve been working off ever since.![]()

We ask Ogden what makes this image so popular, as numerous collectors have bought it at fancy prices. The number of prints in circulation controls fine art prices. But Girls defies the norm, and the huge number of prints sold does not seem to lower the price – in fact, it has steadily increased.

“That’s the million-dollar question, isn’t it?” says the younger Gigli.

“No, Mr. Ogden, that is the 12-million-dollar question,” we interject, [and he laughs] as the image has allegedly sold for $12 million from all the editions.

“I think you’re right with grace,” says the son, born three months before the photo was taken. “I think that it has several aspects to it. I think one is the brownstone [named after brown sandstone, a popular building material in the past], the historic appeal of the brownstone we all love. I think the women in the windows and the contrast to the brownstone emphasize beautifully clean and fresh, with a building that’s being torn down. So, there is a contrast between the old being taken down and the fresh. Women in the windows is one thing, and the scene of New York showing the sidewalk and the Rolls Royce is just all the contrast.

The models were paid $1 each, and they brought their wardrobe and did their makeup.

“Yeah, because a form of payment is necessary to make it legal,” chimes in the photographer.

Girls was first published in the Ladies’ Home Journal, where Ormond got his first photo job at age 17.

“My mother and father took a print [in the early 1990s] down to their gallery [Staley-Wise Gallery in SoHo, New York City] and showed them, and she [Etheleen Staley] thought it was worthwhile. And that was when the first copy of Girls was sold [see below for more details].

So, is this the highest-grossing print or the highest-grossing signed print?

“We’ve only sold signed prints [so far]. I think it goes into both categories because it’s the highest-grossing image because of the number of prints sold, and all of the prints sold had my father’s signature on them.

‘I think he probably signed some on the back when he started. But for the most part, yeah, they’re all in the front. He liked to do that [signed and numbered].

“One edition, maybe 1 through 10? And another edition, maybe 1 through 45? [Each size of print was labeled as an edition.]

“It’s because one day, my father would basically make a print, sell it, and then have one on hand at all times. And eventually, he started selling more prints, and I thought, well, let’s have five prints on hand. That way, we don’t have to do a key print each time and compare color swatches to the other to ensure the color and contrast are good.

“So, we started doing some of that at a time. And then I’d say they’re selling. Let’s print to the end of this edition to make it easier. And then that happened. We created a couple more different-sized editions and always had a couple of those on hand. And it expanded from that.

“I think we counted about a dozen [editions, meaning sizes], but a popular size is mid-30s, 30 inches to 40 inches. People like the low 40s as well. We had 50-inch prints as well, that some people loved. We just had a couple printed at 66 inches [the largest].”

Ogden feels that the image can also work in small sizes even though all the models and other details become relatively small to appreciate.

“It definitely can. It adds more mystery because you must get closer and look harder at it. But it’s still beautiful.”

We asked Ogden how many signed prints are left today since the New York Times article did provide a holiday spurt in sales.

“I’m saying less than 100 [including B&W]. Well, I just put the brakes on all gallery sales. I’m calling a pause until I let the dust settle to see what I have left. I have mostly smaller prints right now, 16×16 inches, and I have a certain number of 27×27 inch prints, and after that, I have to see what I have.

Preserving the Prints

“I created an oeuvre to store the prints properly with temperature and humidity. Every print was signed and wrapped individually in archival foamcore, tissue paper, and archival plastic bags. I put it vertically into my storage area so that when I am ready to sell and ship a print, it’s right there. I pull it out. It’s got the number on it. It’s ready to go. So, they’ve all been inspected. I know the sizes. They’re ready to be boxed and shipped.

“[This way] it keeps certain humidity and certain temperature. Pretty much [what] you want with them. You don’t want it to be 50% humidity because that will cause the paper to do funny things. So, it’s like 35% or 32% humidity and keeping it down in the low 60s [temperature], and that’s what it takes to ensure that the air temperature and humidity are right in them.

What’s the highest price that the Girls has ever fetched?

“Well, we sold a 60×60-inch print [in the past] for $85,000 [The highest sale price when Ormond was still alive was $60,000]. I mean, whatever it was, it’s all higher now. The average just went up from Tuesday [since the NYT article came out], probably 30%. So, I would say that the average of my inventory before the article was $30 to 40,000. [And now] I’m considering adding 30% to that.

So, what happens when the 100ish remaining prints are all gone?

“It’s been brought to my attention, and I’ll decide when I get to that point. It [photogravure] seems like an option to do it right. And it looks like an option to do estate [with a stamp rather than the artist’s signature] prints. But my goal is to end the selling of this image in whatever highest quality way I can.

“I just don’t want to wring every penny out of it. I want to make sure that it retains its integrity. So, if I can do that with estate prints, I may, but I just have to sell these, and I have a feeling that I will be sold out within two years if not six months.

How many prints have sold, and how many prints did Ormond sign?

“I think the article said 600 [have been sold]. And I would say that’s pretty close…plus the 100 I have, so I’ll give a plus or minus, you know, 700, 750, 650. Who knows, somewhere in there?

“I think the reporter [for the NYT] had some type of assignment to research photos, and he was looking at auction houses around the country and world and happened to look at Phillips auction house and sale house in London, and I had a print there for sale. And I think that sparked the whole thing.”

For photographer Ogden, looking at the print is a bit personal as his mother is one of the models.

“And being here, it’s very dear to her because she’s part of that historical event visually,” he says. “She’s part of the history and part of why that image is one of the greatest grossing images of all time. She loved the day that it was and just said how beautiful everyone was to get up into the building. But she said she loves it and is happy it’s doing so well.

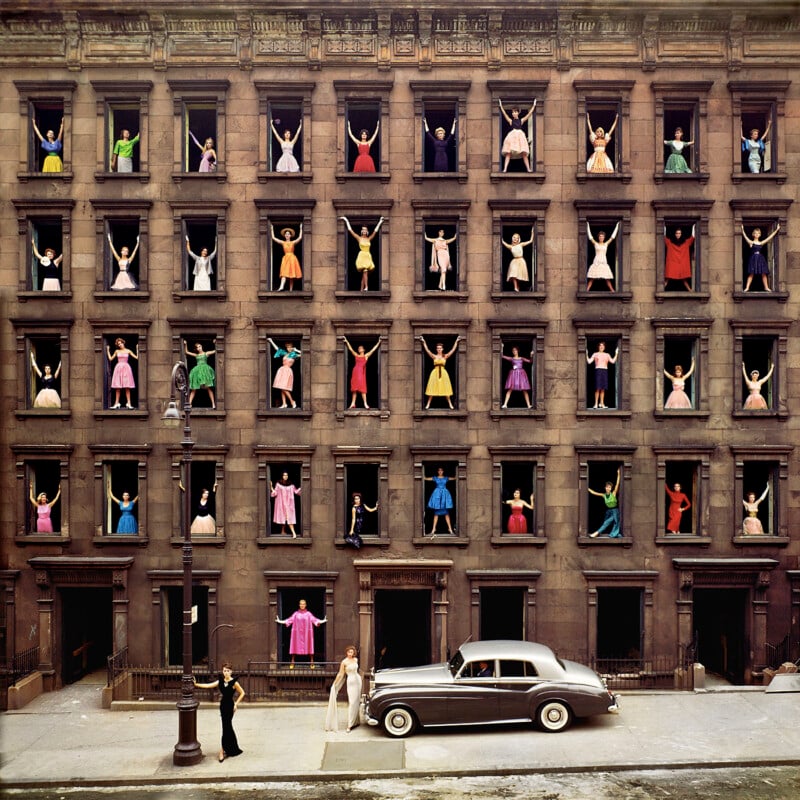

Ormond was born in New York City in 1925. His father gifted him his first camera, which started his interest in the medium. He graduated from the School of Modern Photography in NYC in 1942. During World War II, he was a Navy photographer.

“His experience was fortunate as he was in the Navy, and he went down to, I forget the name of the port near Baltimore, where he was,” says Ogden as he tries to remember his father’s stories. “He was supposed to go out on a ship which was sunk by a submarine.

“His ship turned out to be the admiral’s ship, which never left port and had a full darkroom. So, he would get negatives from the front lines, process them, and show them to the admiral while also doing his personal photography.

In 1952, LIFE hired Ormond to shoot celebrity portraits and cover the Paris fashion shows. One of the pictures made it as a center spread, starting a career as a fashion/portrait photographer for over 40 years.

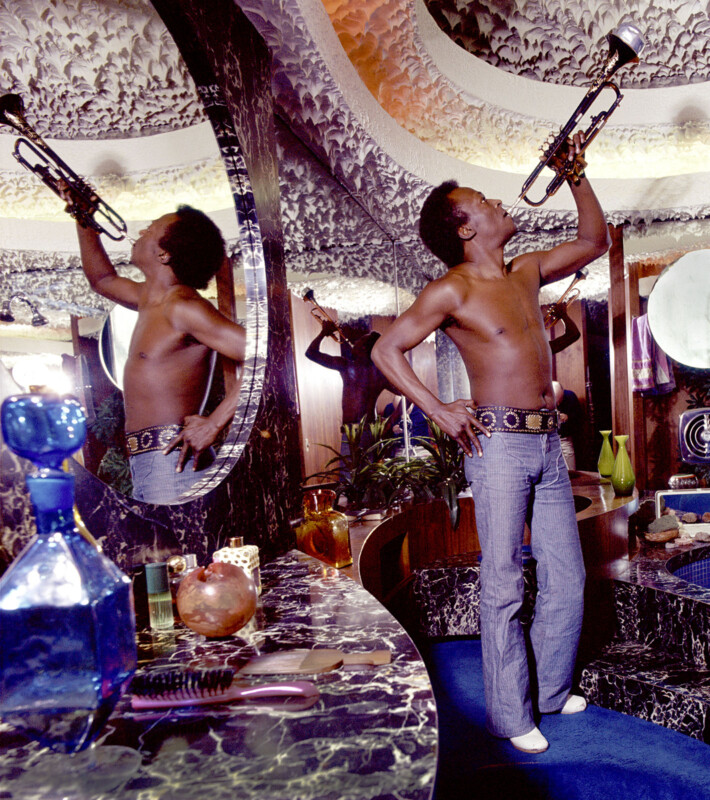

Later, as a photographer, he captured Sophia Loren, Anita Ekberg, John F. Kennedy, Miles Davis, Gina Lollabrigida, Diana Vreeland, Marlene Dietrich, Judy Garland, Louis Armstrong, Laurence Olivier, Alan Bates, and Richard Burton, among others.

He loved his story about JFK and how he came into the studio and was so amiable and kind. He felt wonderful that the President came into his place and that he was able to do portraits of him. That was one of his highlights. I think that was for Time Life.

“One of the Best Images in the World”

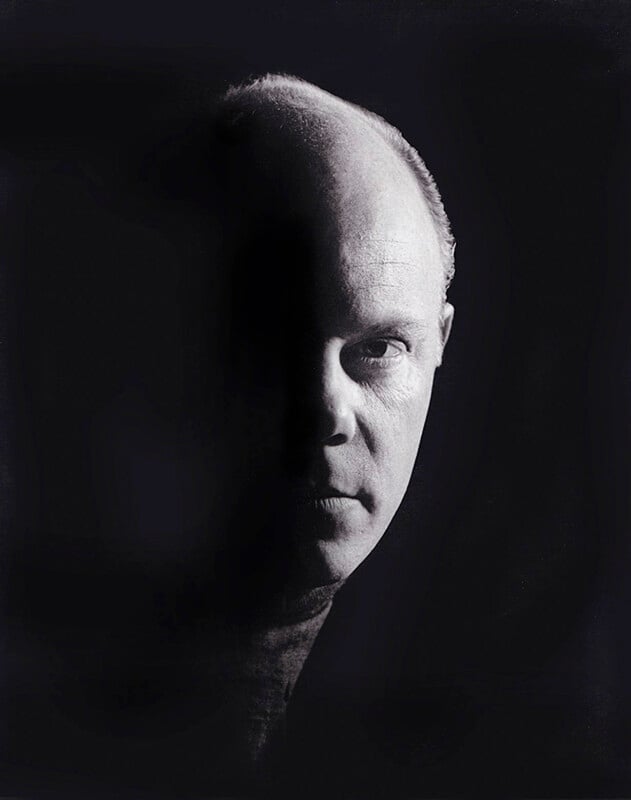

![]()

Lips, the second-best-selling print for Ormond Gigli

“This is one of the best images in the world,” Ogden remembers his father extolling. “And he said that throughout his life. And I believe that in his way, he manifested this.

“He was always amazed that it happened, and then he called it a “happening.” He said it was a happening in history where something happened and that will be around forever. It was just captured in a couple of hours. And he was amazed at that aspect of it.

“In several conversations, [Ormond said] because I still can’t believe it didn’t rain that day. It wasn’t cloudy, it wasn’t sunny, and it had a beautiful cloud layer on top…there was a little divine intervention there [must be as the lighting does not even look like it is shot at mid-day]. And I [Ogden] believe there’s still some divine intervention until this point on selling the image.”

Girls is a great image, but its success and fame today rest heavily on the shoulders of son Ogden. In the last ten years of Ormond’s life, hundreds of prints in various editions (over 70 copies of the 50×50-inch edition) have been created and signed. And sales have very astutely been controlled to galleries and directly to collectors to make it from just a great photo to an art phenomenon.

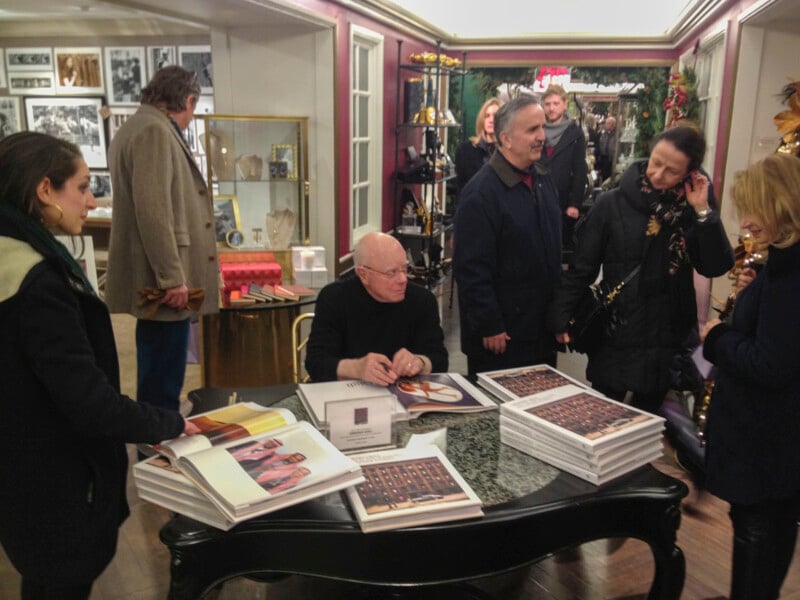

Etheleen Staley at Staley-Wise Gallery, New York City

“The first one we sold was in 1994,” Etheleen Staley tells Peta Pixel.

This was the very first Girls that Ormand Gigli sold as a fine art print.

“It was an excellent picture. We opened the gallery selling fashion photography. That was what we did, and he brought it to us because there’s a lot of fashion in it. And we immediately knew it was a good picture.

Staley could not remember how long it took to sell the first photo, but she went and looked up the records and told us, “Okay, the first one sold for $800! And the more we sold, the more the price went up.”

“Ormond used to come in a lot. He was a nice guy, big burly guy.”

But why does it appeal so much to collectors?

“They’re amused by it.” says the gallerist. “It’s very stylish and chic. And it’s clever. It’s a combination of stylish, chic, clever and witty. So, [it has] got a lot going for it.

“I think we might have a few [prints]. I think we sold one yesterday. We don’t have many here. Usually, we get in touch with the son [Ogden]. We have maybe one or two here.

“[When one] edition runs out, they’ll do another edition – a little bit bigger or smaller. They edition every size, and when they sold the whole edition, they would do another edition in a different size. That was how they operated.

“And that doesn’t work for other photography. No, that’s not how the photography market works. The value is in how few pictures are available, but for this particular picture, it didn’t matter. They made as many as they wanted.

“That is not the case for a photography gallery at all. This was a fluke – his picture selling so many. It goes against the values of the photography market. where the value is in the smallest edition.”

Peter Fetterman at Peter Fetterman Gallery, Santa Monica, California

Peter Fetterman, who has run the gallery for 30 years and has 7,000 prints, “a testament to my addiction” currently in his collection.

“Girls in the Windows makes people feel happy,” Fetterman tells Peta Pixel as he steps out of his gallery for better reception to chat with us on the phone. “It has incredible whimsy and joy. And there’s something really special about it that seems to touch people.”

“I knew him [Ormond] really well. It was self-motivated; nobody commissioned him to do it. And he always told me about the struggles and the problems he had to realize the image, really with no money. So, it was an interesting insight into him, his drive, his energy, his persistence, and his chutzpah!

“We always tend to have it [Girls] up very frequently in my gallery because I know people want to see it and enjoy seeing it. So, whenever we do an exhibition…I often have it in my own office. It makes me smile after all these years. It’s like listening to one of your favorite songs.”

Fetterman has been selling this image since it hit the market over 25 years ago.

“We always used to bring it to the many art fairs we participated in. Often, Ormond came to join us at the booth. And then he did his shtick and told the story personally, which people always love.”

How many prints of Girls has Fetterman sold over the years?

“I mean, it has to be approximately 100 plus, okay, maybe more. Maybe, maybe 150. Maybe two [hundred] and under. I lost count many years ago.

“I think those [27 or 37 inches square] are the sizes that are not too big and not too small. It’s an image that needs some kind of size. I don’t think it works in 11×14 or even 16×20. To have its real impact, it needs to be 27×27 or 37×37.

“I think it’s very much a domestic [for the house] purchase [as opposed to office]. It lightens up people’s homes. If they put this in their dining room, having been told the story by me or whoever, it’s a real icebreaker for people.

“Once you hear the story, it reinforces your initial attraction. That’s why it’s one of those rare images. The image is distributed quite aggressively by his son now.

“Christie’s sold Man Ray’s Le Violon d’Ingre for about $12 million in 2022. So, there are photographs that have sold for higher, but there’s no photo in the history of photography, to my knowledge, that has sold consistently in this quantity and has a desirability that is almost counter-intuitive, counterrational in terms of the quantity of the prints that have been sold.

“It’s the same for Moonrise, Hernandez. Ansel Adams clearly stated he made 1086 prints of Moonrise. So, if you’re logical, you can think why this photo has any value. No photograph has been printed in that quantity, so I think that excels even Girls in the Windows.

“I have ten clients who would buy one now from me for any reason if it was in great condition, you know, for $85,000. And that’s a photograph where you used to call up Ansel himself in the 1970s with ‘Mr. Adams, I’d like to purchase a print of Moonrise.’

“And he would say to you, ‘Dear Boy, send me a check for $400, and I’ll send you the print.’ Now, those same prints are at $85,000-100,000 if you can find them in great condition.

“I think we have a 50×50 inch of Girls in the gallery, which is $75,000. I suppose I’ve invested in that image. Maybe now we have perhaps ten prints. But they keep selling, and Mr. Gigli’s son keeps increasing prices. Sooner or later, the supply will be non-existent, and the demand will be even higher.

Daniel Miller at Duncan Miller Gallery, Los Angeles, California

“Interesting article [in the New York Times], though Ansel Adam’s Moonrise likely has those sale numbers best,” writes Daniel Miller in an email to Peta Pixel.

“30 years ago, the photo market was a fraction of today’s market. Perhaps Art Price or Art Net’s past auction logs can help steer this better.

“Moonrises now are $50-500K. When Harry Lunn was dealing Moonrises in the 1970s, they were $200-$300 a piece.”

Conclusion (Sorry, No Conclusion)

Girls in the Windows by Ormond Gigli in 1960 has seen about 600 prints sold so far, with 100 still available, and that would exponentially increase the overall estimate of $12 million when they are all sold in the next 2-3 years.

Moonrise, Hernandez, shot by Ansel Adams in New Mexico in 1941, has seen 1086 prints made by Adams himself. Since this is 30% more than Girls, the overall sales prices could be higher.

Most Girls are in color, whereas Moonrise is in Black & White, but not that it matters. Also, Ansel Adams’ name has greater recognition than Ormond Gigli’s in the fine art world.

I have not been able to conclude which is the higher grossing print and therefore will open it to you readers to lay down your theories (and calculations) in the COMMENTS BELOW. (And we would be happy to consider a Guest Post on the subject. Send it to me at the contact below)

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photos courtesy of Ogden Gigli